Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Recently, NPR (National Public Radio) ran a story on the importance of sex education, particularly for young people with intellectual disabilities (ID). One alarming reason is the higher rate of sexual abuse and assault within this community versus folx without ID. To help us explore this issue, and how parents, caring adults and educators can approach sexual health talks with young people living with ID, I chat with Nick Winges-Yanez who is a researcher and the Project Coordinator of the Texas Sibling Network at the Texas Center for Disability Studies at the University of Texas. Nick shares her personal connection with ID, which catapulted a career in service, research and advocacy around sexual health for folx living with intellectual disabilities.

Want to connect with Nick? Follow her on Instagram here. Check out her live streams on O.school here. Read her Op-ed published in the Austin-American Statesman here. Learn more about her Sexuality & Developmental Disabilities workshops here. Contact her via email here.

For additional resources on sex education for all abilities:

- Sexuality and Developmental Disabilities Workshops with Katherine McLaughlin

- Teen Vogue: Why Sex Education for Disabled People Is So Important

- Article: #Metoo Must Include the Most Vulnerable People in Texas

- UT Austin’s Texas Center for Disability Studies

And as always:

- Be sure to follow us on Instagram, Twitter and YouTube for regular sex-positive content and updates.

- Sign up for our email list

- Leave a review in Apple Podcasts to let us know how much you’re enjoying the podcast. This gives us great feedback from our community as well as expands the reach and visibility so we can serve more families!

{Soft instrumental music plays as introduction}

{Person speaking}

Welcome to Sex Positive Families where parents, caring adults, and advocates come to grow and learn about sexual health in a supportive community. I’m your host, and the founder of SPF, Melissa Carnagey. Join me, and special guests, as we dive into the art of sex-positive parenting. Together, we will shake the shame and trash the taboos to strengthen sexual health talks with the children in our lives. Thank you so much for joining us!

{Same person speaking}

Melissa Carnagey: “So recently, NPR ran a story on the importance of sex education particularly for young people with intellectual disabilities. One alarming reason is the higher rate of sexual abuse and assaults within this community vs. folx without I.D. To help us explore this issue and how parents, caring adults, and educators can approach sexual health talks with young people living with I.D. I chat with Nick Winges-Yanez, who is a researcher and the project coordinator of the Texas Sibling Network, and the Texas Center for Disabilities Studies at the University of Texas. Nick shares her personal connection with I.D. which catapulted a career in service, research and advocacy around sexual health with folx living with intellectual disabilities. Let’s check it out!”

M.C.: “Alright, well welcome to the SPF podcast! Nick, we are so excited to have you and to dive into the topic today. I’d love for you to share with our listeners what your journey to the work you’ve been doing has been.”

Nick Winges-Yanez: “My journey seems to me is kind of long-winded. I grew up with a sibling, a sister who is labeled with an intellectual disability. And often went to her school meetings and I was always surprised by the curriculum that was being presented because it kinda seemed different from my own curriculum. So, there was that weirdness that I grew up being like, why is it so different? And then when I graduated high school I didn’t immediately go to college, I started working in social services. I usually went towards residential group homes that had adults living in them that had various developmental disabilities. I was in that field for a while and I ended up working in a group home that had men who had developmental disabilities and also sexually offending behaviors.”

M.C.: “Mmm.”

N.Y.: “And that was really a tough house. It had a lot of stigmas associated with it. And when I started working there, there were a lot of rules and training that happened. That seemed to be really scary and then once I started working in this house, I was kinda blown away by the guys that lived there. And one how amazing they were…”

M.C.: “Yeah.”

N.Y.: “And two how their own lives led them to where they were, which often was through a complete lack of any sex education and also mixed with various sexual abuses. During that time I started to learn a lot more about those processes and working with these guys and seeing what that looked like and how different that was and what the sigma associated with them was. So I decided to go back to school so that I had some more agency in furthering this discussion and furthering this work. And when I got to school and grad school, I realized that there was a just a dearth of information. Everything that was either associated with someone who was labeled as intellectual with disability and sexuality was either about sexually offending behaviors or talking about eugenics or talking about how people just generally are asexual. And it just did not jive at all with my own experiences.”

M.C.: “Right.”

N.Y.: “And with the experiences of a lot of people I worked with and I started to kinda do a lot of research and find out where the work was being done, what kinda work was out there. And there were some amazing programs out there, but they were few and far between. And then I started to work with this one man. I was an independent contractor at this point. I was living in Portland, Oregon. And this one man was having a lot of trouble because he personally identified as gay. He did have an intellectual disability and his parents whom he lived with, were very conservative and very, very religious. And did not believe that he could be gay or was gay. And so, he started interacting with some fairly unsafe behaviors because what he did know about gay men were these stigmas. So he was not very safe so I was trying to talk to him and figure this out and his family was very upset that there was any discussion about his sexuality. And they pulled him out of services completely, and said that people who have intellectual disabilities are not gay. They don’t have any sexuality and from that point on there was no contact between my agency and him. It was just this huge turning point for me, that there’s this huge group of people out there who are left to their own devices who have no information possibly no support at all. And I wanted to be someone who could help with that and change that. So, I continued to work on my grad school work which was looking at intellectual disability and sexuality, looking at it from sex-ed programs, looking at sex education, looking at how people have self-advocated for themselves, and what they have said about sex ed and their sexuality. And I’ve come to, I’m working on my Ph.D. right now which is intellectual disability and sexuality as a concept; are completely intertwined. And the way that we generally look at people who have intellectual disabilities is generally associated with sexuality in some way, such as, they are asexual, or we look at their history of eugenics. Or we look at how people are incapable of understanding sexuality or they’re deemed as hypersexual and have sexual offending behaviors. And so, it just started to really blow me away how much they are intertwined and yet we still have so much censorship and limitations associated with just providing any information at all.”

M.C.: “Wow, so you’ve had, it’s a purposeful journey in terms of the personal experience in your own family and then in the work experience and the research that you’re doing. I’m so glad that passionate folx like you exist as advocates to push forward these conversations. Can you define for us what intellectual disability encompasses and especially in relation to developmental disabilities?”

N.Y.: “Yeah, so developmental disabilities is more of an umbrella term that refers to a disability that occurs before the age of eighteen. It has some other facets that go with it. Intellectual disability specifically is looking at, it generally includes, adaptive behaviors and how people can get through daily living tasks through the day, and it generally also includes an I.Q score, which has changed over time. But it is generally at this point considered seventy-five and below, but it’s usually looking at a functional assessment as well. So how well people can be independent in their daily lives or what types of support they need in their life, and that usually speaks to more intellectual disability. And I tend to say labeled with intellectual disability because if you look at history it’s been a term that has changed over time; not just the exact definition but also how we define people. So, we’ve had very hurtful terms that were considered medical terms such as, idiot and moron, and those were considered medical terms at the time.”

M.C.: “Right.”

N.Y.: “And then we moved into mental retardation, which is again not something that we would use now. It has changed into intellectual disability, but I foresee that will eventually change. If you look at history, it’s something that’s inevitable, but we’re constantly trying to label people in this box and then that label just tends to really limit how we see their potential.”

M.C.: “Absolutely, when I was looking at one of the governing organizations leading the thought in advocacy and research. It was AAID dot org, and when I was looking at some of their content, and specifically how to support folx with intellectual disabilities, one thing really stood out for me it said that enhancing the functioning specifically in terms of self-worth, subjective wellbeing, pride, and self-identity. And what spoke so clearly to me there, is that those principles are at the core of what we tend to do when providing sexual health education. So, there’s such a cross over there!”

N.Y.: “There’s a huge, huge cross over! I think it’s amusing when we talk about a lot of work that is being done with people who are labeled with I.D. and we talk about self-determination, and we talk about self-advocacy, and we’re talking about how to encourage independence. And all that seems to be discussed separately in a silo from anything that has to do with sexuality most of the time. And to me that doesn’t make any sense.”

M.C.: “Right.”

N.Y.: “Considering sexuality is just a core part of the human experience. And that it covers so many different parts of how we experience the world. So, it’s how we view ourselves, how we view any of our relationships, whether it is intimate or not with other people. How we see media and how we intake that media, and yet when we’re talking about self-determination and advocacy with people who are labeled, sexuality doesn’t come into that discussion. And I just, I can’t see how we can separate those two.”

M.C.: “Right, so what are the common myths, the common misconceptions around talking to folx with intellectual disabilities about their sexual health?”

N.Y: “Right, so lots of people and these are people who either have no interaction with people who might be labeled or have little, and it includes people who work with or are family of, and they think a lot of people who are labeled with I.D. are asexual.”

M.C.: “Wow.”

N.Y.: “Asexuality is definitely an orientation in ways that people identify, it seems to be assumed of people who are labeled with I.D. that is just who they are. which is not true.”

M.C.: “Right.”

N.Y.: “People often assume that people labeled with I.D. are incapable of understanding sexuality and the nuances of sexuality. And incapable of understanding differences between public and private and relationships and intimacy. Some people think that people labeled with I.D. are more like children and therefore should not be introduced to this world of sexuality, because it would be impure. It would be as if you were tainting a child or sexualizing a child, which again is not true. Because of course people who labeled with I.D. mature and grow in this world, the same as anyone else. And they might need support at different levels, but they still exist in this world. And mature physically at the same rate as anybody, experience hormones, all these different things happening with their body. And they feel love, and it’s something that people just either ignore or avoid or try to say it doesn’t happen.”

M.C.: “What about queerness? In terms of folx with I.D.?”

N.Y.: “Well, unfortunately, this is one of those really touchy topics with people who work in this community or family members. So, a lot of people believe that people who are labeled with I.D. cannot be queer. That it’s not just something that happens. Which again kinda blows my mind.”

M.C.: “Right.”

N.Y: “Because they are people who are part of this world, and this happens to everybody regardless of your ability. As I said I worked with a young man who identified as gay. His family just, inherently against this, and he was confident about it. He identified as this way. He felt it in every part of his body, and he talked about it and he talked about what he found attractive. And this is something that occurs, and yet, we either say well this is because people who are living in say residential facilities are segregated by the gender affirmed. So, that is why they are exhibiting these queer behaviors. This may lead to some instances but that doesn’t mean that’s what the entire experience is. That happened a lot with people I talked about when I was working in different homes, and they would be like, “oh it’s just because they only lived with other people who identify as men” or “they only live with other people who identify as women.” And yet, when they were out and about, and experiencing life, they would still choose this person or this other sex. And I don’t understand how people are saying that people who are labeled with I.D. cannot be queer. It just does not make sense to me!”

M.C.: “Right, dehumanizes their experience.”

N.Y.: “Yes!”

M.C.: “So, what tips can you offer to parents or caring adults of young people with I.D. in terms of how they can foster their sexual health or approach talking about sex?”

N.Y.: “I personally think it’s very similar to talking to any younger person when you’re first talking about sex. You really want to make sure you’re answering the question that is asked, and when you are talking with someone who is labeled as I.D. you wanna make sure you’re being concrete about your answers and what you’re talking about. So, using metaphors is not going to be very helpful and being a little abstract is not going to be very helpful. Using pictures is very helpful, using some sort of prop is very helpful for people. Using simple language. Not using jargon. Bringing up the conversation really without shame. It is very helpful. I think for across the board for anybody despite what your ability is so that it becomes a normal part of life, and we all experience the sexuality. And then that also leads to being comfortable with how your body’s changing or being comfortable with how you, your feelings are changing. I think that, one of the biggest disservices that many people who are labeled with I.D. face is that they have been infantilized or they have been treated as children their entire lives and so that generally means that, that person is headed or told to hug their relatives or friends or whatever so their body sovereignty goes down…”

M.C.: “Yeah.”

N.Y.: “And when I say body sovereignty, I’m talking about that agency that your body is your own and you have th犀利士

e right to say, “No,” to someone touching you, or you touching someone else. And I think that that leads to a lot of blurred lines for people, so, there are a lot of people who think that it’s quote-on-quote cute to hug people who are labeled and that, that’s just sweet. Instead of saying, that’s your body and this is my body and it’s used for these different ways and these different ways at these different times. Instead, we lower that for people currently labeled as I.D. and that their body sovereignty is very low, and that means that their boundaries are very low. And so, when we look at stats that have come up over even the last month of people who have experienced different sexual abuses I think part of that is because we have lowered those boundaries for people over their lifetime.”

M.C.: “Yeah, that’s such a great point. What sex education programs are there? Any that are out there that are addressing folx with different abilities?”

N.Y.: “There’s a public-school education called, FLASH, it’s out of King County in Seattle, Washington. That has a general ed sex-ed program that’s comprehensive, and then they have the special education part that they’ve just revamped, and it’s comprehensive.”

M.C.: “Awesome.”

N.Y.: “Meaning that it takes into account more facets of sexuality. It takes into account people’s faith communities, and their families, and some of their belief systems. It also encourages them to have these discussions and make these choices. It encourages them to look at healthy vs. non-healthy relationships, what consent looks like, different orientations, different gender identities. So, that’s starting to be talked about, but really there’s more I think for adults with intellectual disabilities that’s available. I think that’s because people are more comfortable talking to adults with disabilities vs. kids.”

M.C.: “That’s tough, right?”

N.Y.: “Yeah.”

M.C.: “Because at that point it’s often too late, and when I say too late I just mean some of the adverse outcomes that we’re trying to prepare or prevent. At that point once you reach adulthood it can be harder to change certain behaviors or certain understandings, or certain events that have already taken place at that point.”

N.Y.: “And that is where a lot of advocacy is happening, this is where we’re like, “you know it’s great you want to have these discussions now or these workshops now for adults…” but during that time when they were growing up and having all these questions, and didn’t know what was going on or maybe having these interactions that didn’t feel quite right. We should be having these sexual education discussions then; we should be incorporating it into this growing up time. And I’d say that across the board for I think all kids, you know?”

M.C.: “Yeah! I think that’s the big takeaway here, right? Is that yes, we are using the label of intellectual disabilities because there have been market differences and stigmas, but the big take away that I’m hearing from what you’re saying is that the education needs to not be any different.”

N.Y.: “Yeah.”

M.C.: “The conversation needs to not be any different than what you would approach with any other child of any ability because you are assessing your unique child and where their age is, you know their comprehension level is, their maturity levels are, their curiosities and that can vary child by child. And it has nothing to do with abilities or labels. It’s just purely you looking at your unique child and as a unique human being and trying to meet their needs like you said, early and ongoing.”

N.Y.: “Ongoing! That is exactly what it is, and I think it’s, my people are asking what are some tips you have for talking to families or staff members whatever the case may be. I hesitate because there is no overall general way to approach it, it depends on that person. And I think that’s for anyone that you’re talking to, so if that person then you know how do they communicate? You know, do they use words, do they use a communication board, how does that person understand ideas? And these are all things that come into play when you talk to anybody. How are you going to communicate this information to that person? So that it is effective, and it makes sense to them, and they understand it, and then they can take it and learn from it and then go to the next level. And that’s for anybody, and I think it’s a little bit harder for some people to kinda take that step when we’re talking about people who are labeled with I.D. because there may be different barriers or a few more barriers than people are used to. But that does not mean that that person is incapable of understanding or learning. And in fact, that person might need that information more because other people think that a person is incapable of understanding or learning.”

M.C.: “Exactly.”

N.Y.: “And taking advantage of that situation. And so this is why we need to be having these conversations, instead of assuming that people labeled with I.D. can’t handle the situation. Provide the information in a platform that makes sense for that person and then move on from there. And I just don’t understand why we would keep people from that information, that is so very necessary.”

M.C.: “Yeah, it sounds like the education needs to happen with the parents and caring adults it needs to start there. And addressing their taboos or the myths that they have or the challenging emotions that they might be having, in terms of having these conversations.”

N.Y.: “It does, and I think some parents are very nervous that if they start to have that conversation then it might cause their kids to be really curious and go out and do things and I think that’s something that all parents fear. And it doesn’t, it doesn’t mean that it’s more so for these kids, it’s just that I think parents of kids with disabilities have more fears about different things and maybe they have just entered this world. And I’ve talked to a lot of parents who are like, “you know I want to have this conversation,” or “I would love to figure this out but we are figuring out a communication board.” Or we’re trying to figure out how to get him or her into school or whatever. Those are very real barriers and those are very real supports that need to be addressed. And I would never trivialize those. I would say that this conversation also is a priority that needs to be bundled in with those other things that are going on. Because if we leave it until they’re adults, there’s a lot of missing opportunities that happen.”

M.C.: “Absolutely, this is such a helpful steppingstone bringing these things up and opening up the dialogue. There was a recent NPR article about this, and then you also authored an article, is that correct? With the Austin American Statesman.”

N.Y.: “I did through UT, so I work at the Texas Center for Disabilities Studies and I wrote an op-ed and they sent it to the Statesmen, which was great. I was just so happy that, that conversation is just getting started here, especially in Texas. I want people to be having these conversations and to not be so nervous or scared about it. And I like to put it out there that I am a sibling and I have talked with my parents about this regarding my sister and I’ve had conversations with my sister. And it is hard and it is difficult and my sister is not very interested in this stuff right now. She’s like, “yes, I know where babies come from, I know about this stuff.” Already blew my mother away.”

M.C.: “Awe.”

N.Y.: “But we’re having these conversations and I think kinda putting that out there shows to my sister and to other people with disabilities that we respect them…”

M.C.: “Exactly.”

N.Y.: “As a person. That we want to have these conversations with them, and respect that they know something and respect that they have this sexuality. And I think it’s kinda opened up a new venue between my sister and me, because she knows that she can be like, “I kissed my boyfriend.” And I can sit there and laugh and she gets giddy and she’s like, alright cool.”

M.C.: “Yeah that is no different than the same types of conversations and connections and open dialogue that we seek to foster with all of our young people regardless of their ability.”

N.Y.: “Absolutely.”

M.C.: “We want them to feel safe and comfortable being able to explore their sexuality and their sexual health journey.”

N.Y.: “Absolutely and knowing that they feel safe enough to come to someone. Knowing that they feel safe enough to ask these questions. And then also, you know- I think it’s great that she wants to feel the pitter-patter of having love and you know having that human connection and human touch. I think that’s an amazing gift.”

M.C.: “So, as we wrap up here, what does sex positivity mean to you? How does it play out in your life or the work that you do?”

N.Y.: “Sex positivity to me is embracing sexuality, it is encouraging discussion, it is being open to talking about sex and it’s a wide world of what that means. And how that is expressed and how people interact with that. And not shaming people, not censoring people, or telling people that they’re wrong. I think that that is sex-positivity. and just always knowing that we never know it all…”

M.C.: “Right.”

N.Y.: “And that we’re always learning and that. That is kind of an amazing thing too.”

M.C.: “So what projects do you have going on right now or that you’re looking forward to for 2018?”

N.Y.: “I am actually going to be doing sex ed workshops.”

M.C.: “Yay!”

N.Y.: “For adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities through TCDS. Having a post-secondary program that’s going to be starting up, so we’re going to have some people living in dorms, and we’re going to just do a quick overview of sex ed, relationships, consent. I’m going to be doing a full-on workshop for groups of people who are interested in taking that. I’m also going to be providing workshops for staff members and family members to take kinda the partner course to the courses that self-advocates are taking. And I will… maybe, hopefully, finish my dissertation.”

M.C.: “I think you will. Well, we can help hold you accountable for that, cause it’s obvious you are doing amazing work and it’s so needed. What does TCDS stand for?”

N.Y.: “It’s the University of Texas’s Texas Center for Disabilities Studies.”

M.C.: “Awesome! And so how can people connect with you?”

N.Y.: “Well I work there so if you go to the TCDS site I am on there, and you can contact me through there. I am also on Instagram under “chichi” that is my sex educator name.”

M.C.: “Awesome.”

N.Y.: “And, yeah mostly through TCDS. Because that is where a lot of my work is coming out right now, and I’m trying to work with a lot of the disability community here, so I’m very excited to kind of move into this whole area. I also work with siblings which are very exciting. We just started a sibling group. So we are working with siblings of people who are labeled with I.D.D. and creating kind of a support resource network.”

M.C.: “That’s awesome because as I think as you’ve shared with us that relationship that you can have with a sibling is special and unique. And that’s amazing that you’re considering doing that and providing opportunities for support and to continue the dialogue with siblings.”

N.Y.: “Yes, and I think siblings are kind of the key right now. I think we’re in kind of an odd position because I think a lot of parents enter into this world more of a surprise and a learning curve whereas a lot of siblings have been in this world and always known this world of someone with an intellectual disability. So, we’re kind of in a unique spot.”

M.C.: “And are you working with O.School?”

N.Y.: “I am working with O.School. I have not been as active as I wished I was, but I am a pleasure professional on O.School talking about sex and disability and then just basic human sexuality, so I am on that platform when I get a chance.”

M.C.: “I will offer encouraging words though, that a lot of our listeners are also listeners or pleasure professionals but listeners of O.school. and I know that this topic and the wealth of knowledge that you have to bring to it, your unique voice through a live stream format would be so helpful. So, we will keep an eye out for when you do some live streams! Because I think that again it, these are all conversations that need to be had and myths that need to be busted so we can offer better opportunities for folx with all abilities.”

N.Y.: “Yes, thank you!”

M.C.: “Thank you! Well, this has been amazing. I appreciate your time, and your expertise and you sharing your journey with us. I know that a lot of our listeners benefit from this. So, thank you so much.”

N.Y.: “Thank you so much for having me. This has been just an awesome opportunity, and I am just so thankful that you asked me to do this.”

{Soft instrumental music plays as outro}

{Person speaking}

If you liked this episode and podcast please leave a review on iTunes or GooglePlay so more people can find us. And you can always visit us on our website at sexpositivefamilies.com, there you can shop sex-positive swag in our online store. Connect with us across our social media platforms, join our Facebook community, and learn more resources to help support sexual health in your family. Until next time, I’m Melissa Carnagey, thank you for supporting content that strengthens sexual health talks in families.

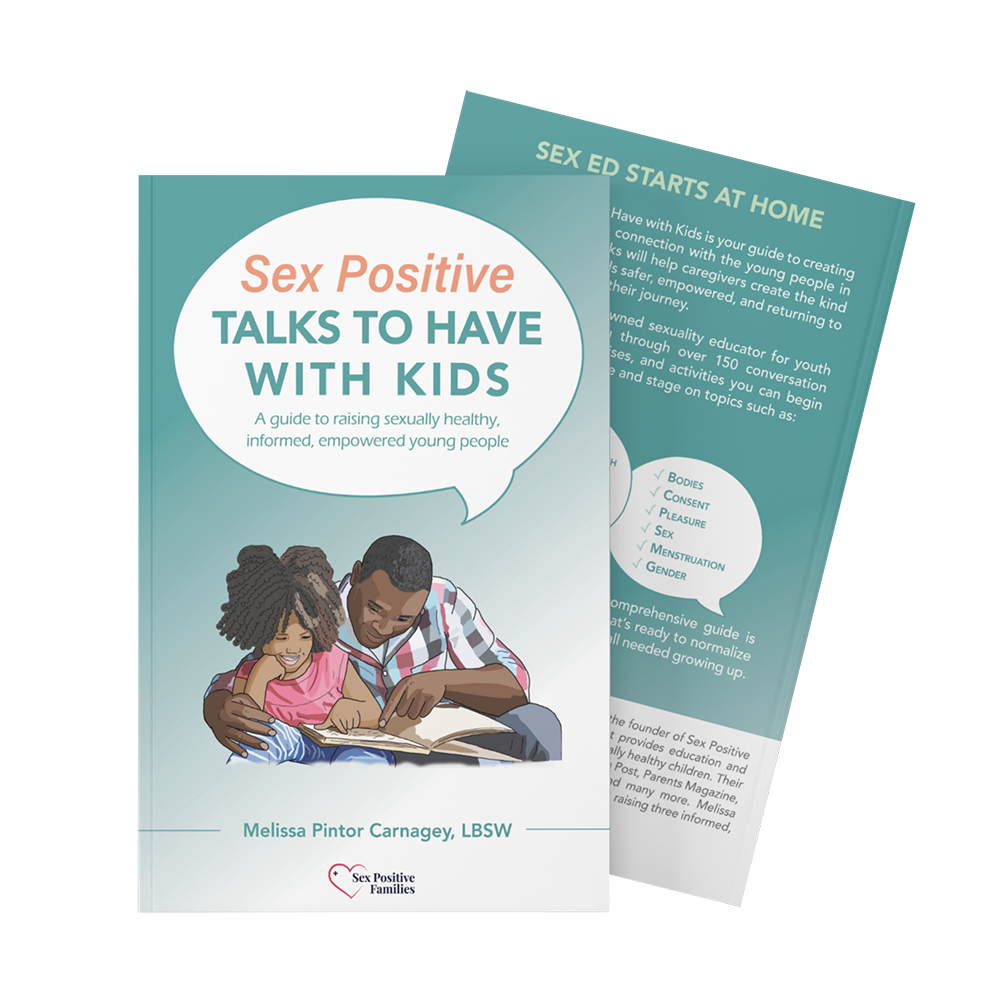

Sex Positive Talks to Have With Kids is the bestselling guide to creating an open, shame-free connection with the young people in your world.

It’s an inclusive, medically accurate, and comprehensive resource that walks you through over 150 conversation starters, reflection exercises, and activities you can begin implementing at every age and stage to normalize sexual health talks and become the trusted adult we all needed growing up.